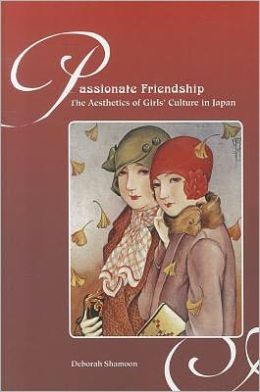

Hagio, Moto. The Heart of Thomas [Tōma no shinzō]. Trans. Rachel Thorn. Seattle: Fantagraphics, 2012.

James Welker

Last year, 2014, marked the fortieth anniversary of the publication of Tōma no shinzō (The heart of Thomas), Hagio Moto’s (1949–-) shōnen’ai (boys love) manga masterpiece. The first installment appeared in the May 5, 1974 issue of Shōjo komikku (Girls’ comic), a magazine targeting middle school girls.[1] Although Tōma depicts both passionate friendships and romantic love between adolescent boys, its publication in a mainstream shōjo manga magazine was not particularly surprising. Even if shōjo manga narratives about romantic relationships between beautiful schoolboys—works that would come to be labeled shōnen’ai—remained risqué no matter how platonic, by the mid 1970s male protagonists in shōjo manga were no longer remarkable. Moreover, earlier experimental works depicting romance between schoolboys had appeared in Shōjo komikku’s offshoot for older adolescent girls, Bessatsu shōjo komikku (Girls’ comic extra). For instance, Takemiya Keiko’s (1950-) Sanrūmu nite (1970, In the sunroom), widely considered to be the first shōnen’ai manga, and Hagio’s own Jūichigatsu no gimunajiumu (November gymnasium), had appeared in 1970 and 1971, respectively.[2] By the time she began serializing Tōma no shinzō, Hagio had become a prominent member of the so-called Year 24 Group (Nijūyonen-gumi) of young female artists who reinvigorated shōjo manga in the 1970s, imbuing it with literary characteristics, and receiving a measure of artistic leeway not afforded to less popular authors.[3]

The manga ran in Shōjo komikku for less than a year and initially failed to appeal to readers. But Tōma no shinzō—alongside Takemiya’s subsequent Kaze to ki no uta (1976–1984, The song of the wind and the trees)—went on to attract a huge number of fervent fans and to play a formative role in the establishment of the shōnen’ai genre.[4] These and other key shōnen’ai works, with their literary allusions and their focus on psychic development and interpersonal relationships, also helped shape the tenor of shōjo manga in the 1970s in general, as Ishida Minori has convincingly argued.[5] This was possible in no small part because the shōjo manga world of the 1970s, including artists, fans, and magazines, was far less segmented than today. Hagio, Takemiya, and other Year 24 Group artists who created popular shōnen’ai manga also produced science fiction, mysteries, and other types of works with narrative and visual similarities to shōnen’ai, which appeared in the same magazines, targeting the same readers.

The shōnen’ai manga of Hagio and Takemiya, particularly Tōma no shinzō and Kaze to ki no uta, are emblematic of the shōnen’ai genre.[6] To be sure, the two are very different works. The relationships between beautiful boy characters in Tōma are chaste compared to the shockingly explicit encounters in Kaze to ki no uta. And Tōma seems all the more platonic when compared to the amateur yaoi and commercial “boys love” (bōizu rabu), or BL, narratives that have followed since the 1980s.[7] Nevertheless, the characters’ expression of attraction to fellow students and, more strikingly, the recurrence of kisses between beautiful schoolboys imbue the narrative with the male–male romance and eroticism that is central to shōnen’ai.

Scholars and critics have long held that in the shōnen’ai of the 1970s and 1980s, bishōnen (beautiful boys) served as a locus of identification for adolescent girl readers, and that the use of male (rather than female) characters, as well as homo- (rather than hetero-) sexual relationships, often in historical foreign settings, provided female readers the means of vicarious circumvention of local gender and sexual norms.[8] True to form, Tōma no shinzō is set in a romanticized and historic if not quite historical German boys’ boarding school populated by bishōnen—a setting loosely based on Herman Hesse’s schoolboy novels and Jean Delannoy’s film These Special Friendships (1964, Les amitiés particulières).[9] The narrative itself is about a victim of abuse, Juli, learning to love and to be loved. Before the story begins, the earnest-to-a-fault Juli rebuffs the affection of a younger student, the feminine and beautiful Thomas. Thomas’s suicide at the opening of the narrative, a suicide motivated by that rejection, devastates the school where he had been beloved for his sweet temperament and beauty. Shortly thereafter, Erich, who is facially nearly identical to Thomas, appears at the school and causes a commotion. Erich’s uncanny resemblance to Thomas is a constant reminder of Thomas’s death and ultimately forces Juli to address his rejection of the absent boy’s affection. Juli and Erich’s relationship, mediated in part by Juli’s roommate and close friend, Oskar, is fraught from the start. In keeping with its Bildungsroman paradigm, however, through this conflict Juli overcomes his inability to love, becomes friends with Erich, and heads off into the world.

I have argued elsewhere that the shōnen’ai in Tōma no shinzō, which had not yet seen much in-depth scholarly attention, probably had a strong effect on readers’ understanding of gender and sexuality in the 1970s. In my earlier analysis, I sought to understand why many lesbians credit Tōma no shinzō, Kaze to ki no uta, and other shōnen’ai manga with playing a key role in their psycho-sexual development, and why they do not similarly acknowledge manga about female–female romance that were published in the same period. In that work, I proposed that the androgynous bishōnen characters are open to being read, consciously or unconsciously, as girls and that the works themselves are open to being read as lesbian narratives.[10]

Re-reading Tōma no shinzō and its various retellings for the present review, however, has drawn my attention back to what is arguably the narrative’s primary theme: the role of love. For Thomas, Juli, Erich, and Oskar, as well as more peripheral characters, the presence, absence, refusal, rejection, or loss of love is formative. It nourishes them and gives them confidence, or breaks them down and helps them heal. While I continue to believe that the relative androgyny of the bishōnen characters and the use of male protagonists in manga targeting adolescent females opens Tōma no shinzō and other shōnen’ai manga to lesbian interpretations, I am grateful to be reminded that what makes this narrative so very compelling is its beautiful, if at times traumatic, depiction of love.

Tōma no shinzō has inspired adaptations by a number of artists and performers, female and male, young and old. Among them is director Kaneko Shūsuke (1955–), whose 1988 live-action re-envisioning of 1999-nen no natsu yasumi (Summer vacation: 1999) features female actors in male roles and is set in a boys’ boarding school in a romanticized and oddly futuristic Japan. A novelization of this film was released under the same title four years later by the film’s screenwriter, Kishida Rio (1946–2003).[12] In the late 1990s, Onda Riku (1964–) published Neverland (2000, Nebaarando), originally planned as a novelized Tōma no shinzō. While the story ended up going in a very different direction, like 1999-nen no natsu yasumi, the work is set in a boys’ boarding school in Japan and focuses on impassioned relationships among schoolboys.[13] Sticking closer to the original narrative, the theater troupe Studio Life has staged renderings of Tōma no shinzō no fewer than eight times since 1996, including a month-long reprise in Tokyo and Osaka last summer, in a theatrical tribute to the manga’s fortieth anniversary.[14] And in 2009, celebrated engineer-turned-novelist Mori Hiroshi (1957–) released his novelized retelling, narrated by Oskar. Borrowing Hagio’s title verbatim, Mori’s text includes illustrations by Hagio and quotes from the manga as chapter epigraphs. Yet even as they present themselves as direct retellings of the Tōma narrative, works by Mori and Studio Life deviate from the original both by nature of their format and as a consequence of the vision of their (re)creators.[15]

The 2012 official English-language translation by Rachel Thorn, The Heart of Thomas, published in the United States by comics and graphic novels publisher Fantagraphics Books, is the latest such retelling, one that indexes interest in the work outside Japan. (This interest is also evidenced by the presence of at least one unauthorized fan translation, or scanlation, that has been available online on since early 2010.)[16] Thorn’s translation is itself inspired by love. She writes that her passion for shōjo manga and for Tōma no shinzō in particular led her to a career as a scholar and a translator of shōjo manga.[17] Her deep affection for Tōma no shinzō is evident in the care she put into its translation. When I first learned that the manga would be translated, I wondered how the translator would deal with Hagio’s overwrought dialogue—words that might appear in adolescent schoolgirl fantasies but would never come from the lips of adolescent schoolboys. Fortunately, Thorn has done an excellent job reproducing the tone of the original, to the extent that readers coming to the translation with little familiarity with shōnen’ai are likely to find the characters’ speech somewhat stilted and implausible. This is entirely appropriate. It is an integral part of the fantasy world that Hagio has produced, and with which her rich illustrations and compelling narrative quickly enthrall readers.[18] In addition, Thorn’s useful if brief introduction helps to contextualize the manga, spelling out the significance of both Hagio and Tōma in the history of shōjo manga.

It is surprising that the translation took so long. Other works by Hagio have been published in English since at least the mid-1990s, some translated by Thorn. Also, BL’s popularity in the Anglophone world has long been firmly established (even if Tōma no shinzō is a world apart from more contemporary BL). Regardless, as someone who teaches about manga and anime in English and who has become uncomfortable assigning unauthorized translations, I am grateful finally to be able to include in syllabi a work so beautiful and moving, with so much to offer my students. And as someone who is deeply interested in sharing the history of shōjo culture, I am grateful that this translation finally makes available in English a work that is paramount to the development not only of BL but of shōjo manga itself.

James Welker is Associate Professor in the Department of Cross-Cultural Studies at Kanagawa University. His research and publications focus on gender and sexuality in postwar and contemporary Japan.

[1] Hagio Moto, Tōma no shinzō (The heart of Thomas) (1974; reprint, Tokyo: Shōgakukan Bunko, 1995). On the target audience of Shōjo komikku and other shōjo manga magazines, see Jennifer S. Prough, Straight from the Heart: Gender, Intimacy, and the Cultural Production of Shōjo Manga (Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press, 2011), 10–11.

[2] Takemiya Keiko, “Sanrūmu nite” (In the sunroom), in her Sanrūmu nite (1970; reprint, Tokyo: San Komikkusu, 1976); Hagio Moto, “Jūichigatsu no gimunajiumu” (November gymnasium), in her Jūichigatsu no gimunajiumu (1971; reprint, Tokyo: Shōgakukan Bunko, 1995). On the emergence and development of shōnen’ai, see James Welker, “A Brief History of Shōnen’ai, Yaoi, and Boys Love,” in Boys Love Manga and Beyond: History, Culture, and Community in Japan, eds. Mark McLelland, Kazumi Nagaike, Katsuhiko Suganuma, and James Welker (Jackson: University of Mississippi Press, 2015), 42–75, particularly 44–51. On the target audience of Bessatsu shōjo komikku, see Prough, Straight from the Heart, 11.

[3] The Year 24 Group, sometimes known as the Fabulous Year 24 Group (Hana no nijūyonen-gumi), derives its name from the fact that most of this new generation of artists were born around the year Shōwa 24, that is, 1949. In English, they might appropriately be called the “Fabulous Forty-Niners.”

[4] Kaze to ki no uta (The song of the wind and the trees), 10 vols. (1976–1984; reprint, Tokyo: Hakusensha Bunko, 1995). Hagio recalls that Tōma no shinzō initially failed to appeal to readers and was almost cancelled. But the editors of Shōjo komikku let her finish the story on account of the runaway success of her Pō no ichizoku (The Poe clan) (1972–1976), 3 vols. (Tokyo: Shōgakukan Bunko, 1998). See Hagio Moto, “The Moto Hagio Interview,” by Matt Thorn, The Comics Journal, no. 269 (July 2005): 137–75, 166, as well as Matt Thorn’s introduction to his translation of the work. Tōma no shinzō clearly garnered significant popularity by the end of its run, however, evidenced by its release in book form soon after its serialization.

[5] One of Ishida Minori’s key points in her Hisoyaka na kyōiku: “Yaoi/bōizu rabu” zenshi (A secret education: The prehistory of yaoi/boys love) (Tokyo: Rakuhoku Shuppan, 2008) is that shōnen’ai works such as by Hagio and Takemiya helped shōjo manga develop the literary qualities for which it became known in the 1970s.

[6] I make this point and analyze Tōma no shinzō and Kaze to ki no uta in James Welker, “Beautiful, Borrowed, and Bent: ‘Boys’ Love’ as Girls’ Love in Shōjo Manga,” Signs, vol. 31, no. 3 (2006): 841–70.

[7] The history of the development of and distinctions among shōnen’ai, yaoi, and boys love are mapped out in Welker, “A Brief History.”

[8] The body of scholarship and criticism making this case, often supported by statements by the artists themselves, is extensive. For representative criticism see Fujimoto Yukari, Watashi no ibasho wa doko ni aru no: Shōjo manga ga utsusu kokoro no katachi (Where do I belong? The shape of the heart reflected in shōjo manga) (Tokyo: Gakuyō Shobō, 1998), particularly the section, “Onna no ryōsei guyū, otoko no han’in’yō” (Androgynous females and hermaphroditic males), 130–76. Fujimoto has more recently published a clarification of her original argument, distinguishing between shōnen’ai and later male–male homoerotic genres. See “Shōnen’ai/yaoi, BL: 2007-nen genzai no shiten kara” (Shōnen’ai, yaoi, and BL: From the perspective of 2007), Yuriika, vol. 39, no. 16 (December 2007): 36–47, revised and translated as “The Evolution of BL as ‘Playing with Gender’: Viewing the Genesis and Development of BL from a Contemporary Perspective,” trans. Joanne Quimby, in McLelland et al., Boys Love Manga and Beyond, 76–92.

[9] Les amitiés particulières, directed by Jean Delannoy (Paris, France: Progéfi and LUX C.C.F., 1964). The links between Hesse’s Bildungsromane and the shōnen’ai narratives of Hagio (and Takemiya Keiko) are spelled out in numerous places. The most thorough discussion can be found in Ishida, Hisoyaka na kyōiku. Les amitiés particulières as a major source of inspiration for this narrative has been discussed by Hagio in multiple interviews. In English, see Hagio, “The Moto Hagio Interview,” 161, and Thorn’s introduction to this translation.

[10] Welker, “Beautiful, Borrowed, and Bent.”

[11] Hagio Moto, Hōmonsha (The visitor) (1980; reprint, Tokyo: Shōgakukan Bunko, 1995); Hagio Moto, “Kohan nite: Eeriku jūyon to hanbun no toshi no natsu” (At the lakeshore: The summer of fourteen-and-a-half-year-old Erich), in her Sutoroberī fīruzu (Tokyo: Shinshokan, 1976), 15–42.

[12] 1999-nen no natsu yasumi (Summer of 1999), directed by Kaneko Shūsuke (Tokyo: New Century Productions, 1988); Kishida Rio, 1999-nen no natsu yasumi (Summer of 1999) (Tokyo: Kadokawa Bunko, 1992).

[13] See the author’s afterword in Onda Riku, Nebaarando (Neverland) (2000; reprint, Tokyo: Shūeisha Bunko, 2003), 269. The novel was serialized in Shōsetsu Subaru between 1998 and 1999 before being published in book form the following year.

[14] Studio Life also staged the prequel, Hōmonsha, in 2010 on alternate days during a staging of Tōma no shinzō, as part of the group’s twenty-fifth anniversary celebration. For details, refer to the troupe’s website.

[15] While I was only able to watch one performance of Studio Life’s Tōma no shinzō, which was insufficient to compare adequately the stage production to the manga, it did seem to be following the original story quite closely, down to the reproduction of dialogue from the manga. Mori’s Tōma no shinzō, on the other hand, changes certain portions of the storyline, enabling Oskar to narrate events for which he was not present in Hagio’s version.

[17] Hagio, “The Moto Hagio Interview,” 139.

[18] The one issue I have with Thorn’s translation is, in fact, not specific to this translation but rather an ongoing source of annoyance I have with translated manga in general: the rendering of the frequently used, very evocative Japanese onomatopoeia into natural sounding English. Thorn’s translations of onomatopoeia that represent sounds (giongo) either follow what have become established conventions in manga translation or are reasonable approximations of the sounds for which no onomatopoeia exist in English, while his translations of onomatopoeia which represent physical movements or states (gitaigo) are accurate. In both cases, however, the effect is often awkward, unnatural sounding English, “klangs” and “klaks” and “tmp tmp tmps” which distract from the beauty of the text. The visual, physical nature of the manga page unfortunately does not seem to afford translators the option of rephrasing, available to translators of prose.